Measles was declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, but declining vaccination rates have led to a resurgence. The country is now facing what could be the largest outbreak in six years, with cases spreading across Texas, New Mexico and other states.

The outbreak began in January 2025 in West Texas and quickly crossed state lines. By late February, a six-year-old unvaccinated girl died of measles-related pneumonia—the first U.S. measles death since 2015 and in early March, an unvaccinated adult in New Mexico also succumbed to the disease. Over 300 cases have been confirmed so far, mostly among unvaccinated school-aged children, and the cases continue to rise.

Despite the availability of a safe and cost-effective vaccine, misinformation continues to drive outbreaks, endangering lives. This resurgence highlights the importance of staying informed about the disease, understanding its complications and debunking common myths.

Keystone Infectious Disease’s Medical Director, Dr. Raghavendra Tirupathi, and medical students studying under him, Neha Adepu and Hemanth Kesani, discuss what you should know in today’s “Take Care” article.

Measles: Not Just a ‘Kid’s Disease’

Measles, aka rubeola, is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus. Although known to classically target kids below 5 years of age, anyone with low immunity can catch it, especially pregnant women. Historically, it has hit hardest in communities struggling with poverty, overcrowding and conflict, especially in developing regions like Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Breathe It, Touch It, Catch It—Measles Doesn’t Wait for an Invite!

Measles spreads like gossip—fast and through the air! The virus lingers in nasal and throat secretions and is released in droplets from coughing and sneezing. It can stay in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours, waiting to infect anyone who breathes it in or touches their face after contact. Once inside, it starts in the respiratory tract and quickly spreads throughout the body. A whopping 90% of unvaccinated people exposed to an infected person may catch measles, with most cases in the U.S. being brought in by international travelers and spreading to the unvaccinated.

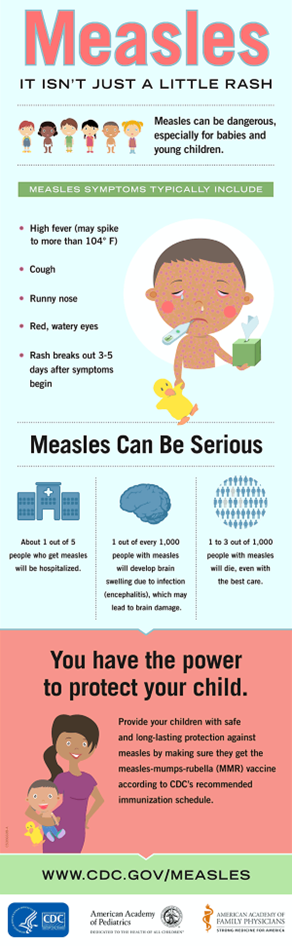

Spot the Spots: Symptoms You Shouldn’t Ignore

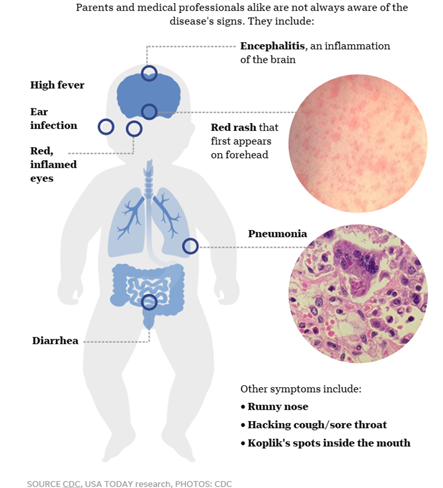

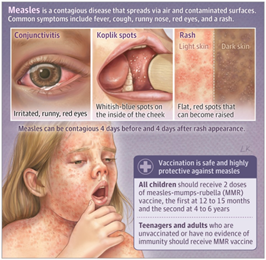

Symptoms usually show up 10 to 14 days after exposure, but sometimes as late as 21 days. It starts with a fever (over 101°F), cough, sore throat, runny nose and watery red eyes. Loss of appetite, diarrhea and ear infections may follow. Then comes the rash three to five days later. It begins as a flat rash on the forehead or scalp and spreads down to the neck and trunk. On lighter skin it appears red, but on darker skin it may look purple or darker. The rash rarely itches and can blend into larger patches. Infected people are especially contagious for four days before the rash begins, and up to four days after the rash begins. It is advised to stay home during this time to prevent transmission. A telltale sign is tiny bluish-white specks called Koplik’s spots, which may appear inside the mouth 2–3 days after symptoms begin, although they often vanish just as quickly.

No, Measles Doesn’t Just ‘Go Away’

Measles is more than just a pesky rash—it can lead to dangerous, life-threatening complications. About one in five unvaccinated kids with measles end up in the hospital. Of those infected, one to three in every 1,000 children may die from severe respiratory or neurological issues according to CDC. Pneumonia is the most common cause of death, affecting one in every 20 children.

But the risks don’t stop there. Measles can cause rare but serious complications like brain swelling (encephalitis), convulsions, deafness, blindness, intellectual disabilities and even long-term immune system damage. In pregnant females, it can increase risk of premature birth and low birth weight in babies. Even worse, the virus can attack the brain years later, causing fatal Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE), especially if a child has contracted measles before age two.

Unvaccinated people, babies under one, pregnant women and those with weak immune systems are more likely to have serious complications from the virus. Kids under five and adults over 20 are also at higher risk, along with malnourished children, especially those with low vitamin A.

Diagnosis and treatment of measles: Comfort Over Cure

To confirm measles, serology testing to detect antibodies or an RT-PCR test from a throat or nasal swab are usually used. Sometimes even a urine sample can be done to confirm the viral RNA.

There is no particular treatment for measles. The management largely focuses on symptomatic relief. The patient is to be kept hydrated, follow a healthy diet, and follow precautions to prevent the spread. Antibiotics may be given for secondary infections like pneumonia and ear infections. All infected individuals are given vitamin A (two doses, 24 hours apart) to shorten the course of illness and reduce the risk of death.

Vaccination: Your Best Defense Against Measles!

Before the lifesaving measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, major epidemics hit every two to three years, causing nearly 2.6 million deaths annually worldwide. Fast forward to today, one dose of MMR (Measles, Mumps and Rubella) vaccine gives you 95% protection, and two doses provide 97% lifetime protection against measles. Even if a vaccinated person does catch measles, symptoms are usually mild, and complications are rare.

The first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years of age. Adults receiving the vaccine should receive the two doses 28 days apart.

The MMR vaccine is generally safe, with only minor side effects like a sore arm, low fever or temporary swelling. Serious reactions, like high fever or seizures, are extremely rare. No booster doses are needed—two full doses are all it takes for long-term protection!

The MMRV vaccine, which also protects against chickenpox (varicella), is available for kids aged 12 months to 12 years.

Who Should Roll Up Their Sleeves for MMR?

Apart from children, all unvaccinated adults over 20 born after 1957 (when measles was widespread) should get the MMR vaccine. Especially those who are international travelers, healthcare personnel, college students, close contacts of immunocompromised individuals or those with HIV and those at higher risk of contracting the disease should be vaccinated to stay protected, particularly during outbreaks.

It takes two to three weeks for full protection, so vaccination should be completed at least two weeks before traveling. Women of childbearing age should also get the vaccine before pregnancy and wait a month before conceiving. For people who were born before 1968 and got the old, inactivated measles vaccine or are unsure of the type of vaccine they got, a dose of the current MMR offers protection.

Who Should Skip the MMR Shot?

Some folks should steer clear of the MMR vaccine. This includes infants younger than 6 months of age, those with severe allergies to the vaccine or its components, pregnant women or those planning pregnancy within a month, and anyone with a weakened immune system due to conditions like cancer, HIV or organ transplants. People who have had recent blood transfusions, tuberculosis or are very ill cannot be given the vaccine according to CDC. The MMRV vaccine should be avoided in those having a history of seizures (or a family history) and if they are on aspirin (salicylates). It’s best to always check with the doctor first.

Think You’re Safe? Check Your Immunity!

People who have received two doses of the vaccine have lifetime protection. One dose of the vaccine is enough to protect preschool children 12 months to four years of age and adults who are low risk. Serum titers can be used to confirm immunity in people who are unsure about their immunity, were infected in the past or were born in the US before 1957 when measles was very prevalent. If the titers don’t show immunity, a vaccination can easily fix that!

Measles 101: What to Do If You Think You’re Exposed?

If exposure occurs, even among immunized individuals, a 21-day exclusion from childcare, school or work may be required. Healthcare providers should be contacted before scheduling an appointment to ensure proper precautions are taken.

Precautions to prevent spreading disease, such as covering the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, washing hands frequently, not sharing drinks or utensils and disinfecting touched surfaces should be followed. A doctor should be contacted if symptoms worsen.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: Timing Is key!

If unvaccinated individuals are exposed, the MMR vaccine should be administered within 72 hours to boost immunity. However, if an individual is severely immunocompromised, pregnant or under six months, the vaccine should not be given. In such cases, intramuscular or intravenous immunoglobulins should be administered within six days of exposure, particularly in high-risk environments such as households, daycares or classrooms. However, immunoglobulins are not as effective as the vaccine itself.

Debunking common Measles Myths

Cod Liver Oil: a miracle cure

Cod liver oil and vitamin A are great, but they only help prevent complications in malnourished kids—not treat measles itself.

Measles is only for kids

Measles loves the whole family! While kids (5-17 years) are the main targets, immunocompromised adults often get it too.

Vaccines cause Autism

There is no scientific evidence linking vaccines to autism. That myth has been debunked by researchers worldwide.

Vaccines are not effective and safe

Vaccines are not just effective, but also safe! The measles vaccine is one of the best defenses against this disease.

Breastfeeding After the MMR?

You can breastfeed without worry after the MMR vaccine. Your baby won’t catch anything from you through breast milk.

Can I take the MMR vaccine when I have a severe illness?

Mild colds? Go ahead and get vaccinated. But if you’ve got a raging fever, wait until you’re feeling better.

Measles infects animals too!

Animals cannot contract measles—only humans can spread it. So, no need to worry about your dog catching it!

In the era of medical advancements and vaccines, the outbreak of measles in the U.S. highlights the serious gaps in vaccine access and acceptance. Measles being highly contagious could be the first one to rear its ugly head, but it might just be the tip of the iceberg, and more vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks might follow suit. This should be a bright red warning sign that we as citizens and healthcare officials should pay attention to and prevent further public health disasters.

In the light of this outbreak, one must consider the impact misinformation has and that combating it is as crucial as medical intervention to prevent further spread of infections and deaths.

Summary

Measles, once eliminated in the U.S., is making a comeback due to declining vaccination rates. This has led to a significant outbreak in 2025 that has spread across multiple states and has even resulted in deaths, primarily among unvaccinated individuals. Despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine, misinformation continues to fuel the spread of the disease. Measles is highly contagious and can lead to serious complications, including pneumonia, brain swelling and even death. Vaccination with the MMR or MMRV vaccine is the best defense, providing lifelong protection for most people. It’s crucial to stay informed, vaccinate and debunk myths to prevent further outbreaks.

This article contains general information only and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis, treatment or care by a qualified health care provider.

Click here to learn more about Keystone Infectious Diseases.